Miki, Atikocan Ontario, 1961

Miki, Atikocan Ontario, 1961 Dancing was not something I was exposed to in my childhood. As an isolated immigrant family moving frequently from one Canadian town to another, we were never part of any cultural events that might involve dance. My parents knew how to dance but I never saw them dancing. In later years, I learned that my father would join singles dance clubs to meet women. I imagine him as a smooth operator. If they became a couple, he would stop going out. My mother, in her 70s radical artsy feminist days was attracted to folk dancing, she was enthusiastic, but not very skilled. I take after my mother.

My mother enrolled me in figure skating, which I loved and which I did for two winters. Without a car, this was made possible partly by the proximity of the rink to our home, only a ten or fifteen minute walk. In a small Saskatchewan city boy’s figure skates were unavailable, and I had an early experience of the mutability of gender. My mother had to buy a pair of used girl’s skates, and paint them black, and I clearly remember my wonder at the simplicity of the transformation. I loved figure skating, and especially performing. We would travel to neighbouring towns with our end of year show, and I vividly remember the atmosphere of female camaraderie on the ride home, late at night, in the bus.

At the end of grade 7, new in a larger prairie city, I became friends with some of the girls in the class, and they invited me to a year-end party held in the garage attached to one of their houses. We played 45s on a portable record player, my favourite being The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” with “Fool on a Hill” on the flip side. The girls taught me to dance the twist and we got high by hyperventilating and hugging each other’s chest from behind until we got dizzy or passed out. I remember the softness of the girls’ angora sweaters. I was in heaven.

From being an introspective, artistic immigrant kid, I blossomed in the post-hippie years of the early 70s as an anarchic “freak” as we called ourselves. I grew my hair and didn’t mind being called a girl. I loved to lose myself in a drug-fuelled ecstasy, dancing to rock music, wishing I could have been at Woodstock. I hitch-hiked across the country, went to sit-ins, played the guitar and sketched portraits of musicians in coffeehouses.

I attended a couple of wedding dances, and enthusiastically learned basic polka and waltz steps, and when I married at 19, I was able to dance at our wedding. As I got older, I found less opportunities to dance. My second, common law spouse didn’t like dancing. I struggled to establish a career, first as a sculptor, then as a scenic designer for theatre. I envied the actors the release of their movement warmups, but I felt inhibited, and conformed to the expectations of the male dominated art and theatre world of the 80s.

In the 90s I began dancing again with my third spouse and second wife, who loved to dance and had danced with a Catalan folkloric troupe when she was younger. We decided to take ballroom dancing classes together. It almost broke up our marriage. In retrospect, maybe it marked the beginning of the lack of communication that led to our eventual separation. I have a good sense of rhythm, but she was good at learning the steps, and it seemed everything I did was wrong. Yet when I danced with other partners it went well. The instructor danced with her, and commented that she should follow, but she denied that she was leading. I felt that she was trying to prove that dancing was something she could do better. This put a damper on my dancing for a long time.

Many years later, having difficulties learning swing dance a from a friend, he suggested I try the role of follow. With him leading, all of a sudden it began to work for me. Later, I took a queer ballroom dance course, and insisted on the role of follow. I found I was making progress, but the class only lasted one season. Even in that queer setting it was hard to find partners to lead with me. Regular ballroom classes would have been impossible. Now that I live as a woman, and I’m not so easily read as trans, I might have more luck.

At 49 aging and death were on my mind. My mother had advanced Alzheimer’s and I had been her primary caregiver for the previous three years. I was unhappy. I had left my career as an unconventional theatre consultant in the high stress, macho world of the Barcelona construction industry. I cut my long hair short, stopped wearing leggings and t-shirt dresses and straightened my image. I was offered a full time job as exhibits designer for a Saskatchewan museum, which I accepted in order to pay the mortgage and fund my young family of two kids. I thought my wife and I were getting along, we generally agreed on lifestyle and childrearing, though I was sexually frustrated and communication wasn’t good. My health was deteriorating. I was getting old. I had arthritic pains and my posture was getting worse. I decided that I had to do something about it before I turned 50. I was not interested in going to a gym. I thought about dance, about exercising with music. Not ballroom dancing, but something creative. I had seen advertisements for the “Big Fat Ass” creative dance classes, but when I inquired I was told it was for women only.

My mother’s decline was particularly tragic. Like many intelligent and creative women she had to put her aspirations on hold while she dealt with a husband, and then, as a single mum, raising 3 children on the brink of poverty. She persevered, and took night classes while working full time. In 1968 we moved to the larger city where she went to university and eventually attained her Masters degree and became a sessional lecturer. She began to write when she retired but Alzheimer’s prevented her from continuing. It was painfully clear to me that if I really needed and wanted to dance, it would not be wise to put it off. So at 49, when a friend, a master of the art of mime, needed another person to sign up for movement classes he was offering for our unschooled children, I asked for Friday afternoons off work and joined the class. I did that for 3 months and got used to doing difficult and ridiculous things with my body in the company of young people. A few days before Christmas of 2006 my mother died.

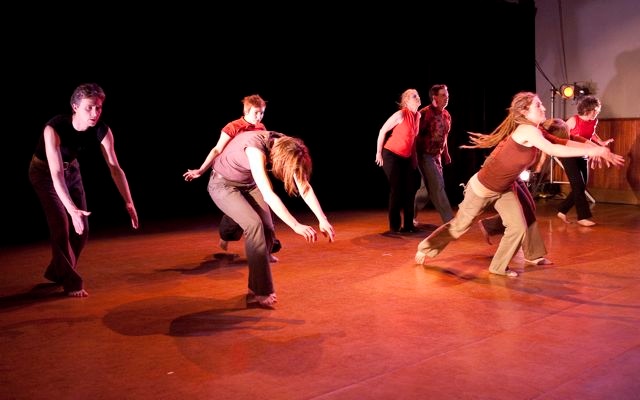

I took Modern Dance classes for a little over 3 years with my first instructor. The other students were young women, less than half my age. It was challenging for me, learning the basic Graham techniques. I was clumsy and felt foolish. My body would not bend right. I could not sit with my legs out and a straight back. I lost my balance. I could barely remember the first moves in a sequence. Hardest was letting myself be ridiculous. How difficult, and liberating it was to lose my dignity.

I persevered. I was getting stronger. It took a long time before I felt my dance technique was improving, but I soon noticed it was easier for me to straighten my posture and to sit on the floor without a backrest. When out, or at a party I was more apt to dance if music was playing, even if I felt it might not be socially approved. An occasional visitor began coming to the improv group, a younger woman with dreadlocks by the name of Kyle. She danced with me in a way that gave me more confidence, and I began to learn how to communicate with my body.

2009

2009 I was coming full circle as an artist. My early professional work, site specific sculpture and art happenings, had a performative element. In the intervening years I explored theatrical performance from backstage as a scenic designer and a designer of lighting and costumes. I worked for a decade in Barcelona designing and renovating theatre buildings, and teaching the history and theory of performance spaces. Back in Canada, I helped translate a script, and collaborated on producing shows with a small company. Around the time of my first dance performance, I brought my mime training into play by accepting a non-speaking role in one of our theatre productions. After decades behind the scenes I was transitioning to being a performer.

The play was about clowns who perform for the Fuhrer’s birthday in wartime Germany. My character represented an imaginary shadow to the lead clown. All the other actors playing the clowns were clean shaven. The actor playing the Gestapo officer had a moustache. Since my 20s, in an attempt to appear more masculine, I had worn a goatee. I shaved it off. Clean shaven, I decided it was my opportunity wear a dress for Halloween. After applying make-up, I fell in love with the woman I saw in the mirror.

I was feeling more graceful and losing my inhibitions about moving my body. I was feeling myself as feminine, and found occasions to dress as a woman when going out dancing with my boyfriend. Losing my inhibitions was allowing me to explore my female self. From childhood my mother had assured me that feeling both female and male was normal, but without realizing it, in an attempt to succeed in my career and as a father, I had been trying to embody society’s idea of masculinity.

Men can dance, and lose their inhibitions without becoming less masculine. In my case it freed me from pretence, and allowed me to blossom as female. I began to feel more authentic, and able to express myself in ways I had not been able to before. I felt like my humanity had been curtailed, that my full potential had been suppressed. Dance improved the health of my body, focused my mind, and liberated my spirit.

My first Modern class was challenging and fun, but not very rigorous. The first season my wife also attended, a dangerous experiment to add to the other she had encouraged me to try, that of having a boyfriend. I realized that I liked Modern Dance, and she realized she preferred something with more structure. I continued, but after 3 years I needed something more challenging.

I attended a modern dance workshop with a vivacious and inspiring woman who had begun a modern dance company at a studio I frequented. She offered no regular modern dance class, but taught a weekly ballet class she described as “organic ballet”. The level was listed as intermediate, but she encouraged me to try, suggesting I follow as much as I could and to simplify if I had to. I found her so inspiring I decided it would be worth it just to listen to her. I attended ballet with her every weekend for the next two years. She insisted on us trying to feel the joy of dancing, even when doing simple exercises at the barre, and I began to strive for grace in my movement. At her invitation I began joining her company training sessions a couple of days during the week. I got used to struggling my way through the barre exercises, then trying some of the centre routines until I got in the way, then working on the bits I could remember in a corner, or stretching while I watched and listened. It was humbling, but thrilling when she eventually began to comment on my improvement.

| Kyle, the younger woman at my improvisational dance group had begun attending more frequently, and she introduced me to a dance form called Contact Improv. She invited me along with her and another dancer to a weekend workshop in a neighbouring city, a day’s drive away. We went in my car, and all got along well, stopping to pee, explore and dance in the landscape. We swam in the Red Deer River. The instructor was Martin Keogh, an exceptional person and teacher, and I learned that Contact Improv was more than a dance form. I was introduced to a new awareness of my body, to gravity and to space. With no set steps, I learned a heightened level of communication with my dance partner. We drove back in the night, sharing intimate conversations. |

Dance saved me. Dancing, I am myself, I am human, I celebrate life. I continue to be sustained by dancing

RSS Feed

RSS Feed