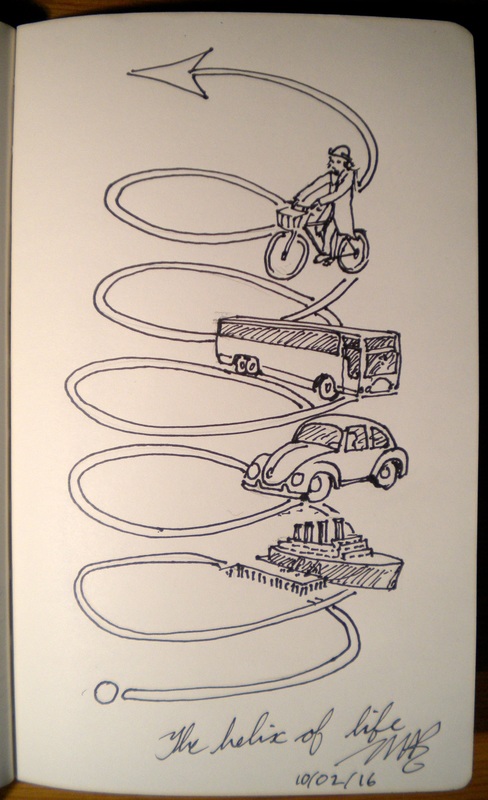

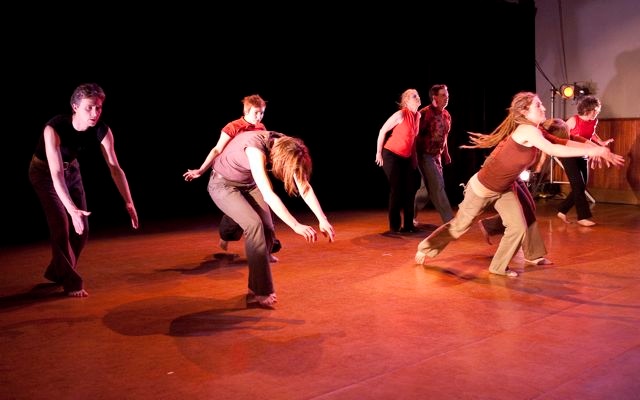

I’m preoccupied. With contradictions. And Contradictions, the name of the show I spent the previous year helping to create in collaboration with fellow dancers Karla Kloeble and Mitchell Larsen. And Contradictions, the working title of the book I have decided to begin writing. I have about 40,000 words, a good start, but I’ve slowed down the past few months, uncertain of how best to proceed.

I continue to visit; twice a year now, to dance Contact Improv and to visit my son in Toronto and my daughter in Montreal. I want to live in Montreal, but I want to live in Saskatoon also, sharing a house with a good friend, with my cheap and beautiful downtown studio, the berry bushes and the beaches on the river.

Contradictions, the performance, was a success. We worked on it for a year; it opened at the end of August 2016 for three shows, two sold-out and one well attended. Plus all the works in progress and excerpts showings. But I was never satisfied. It felt like we’d reveal one contradiction, peel it away, and underneath there’d be another layer, like onion skins; under each layer another seemingly whole onion.

For me the contradiction between being born and living the first part of my life in a male body and now living as a woman was one of the central themes to the performance. But I was always conscious of the next level, my inability to reconcile my radical feminist views with the philosophical implications of claiming to be a woman.

What is a gender identity? After campaigning for human rights protection for gender identity and gender expression, both provincially and federally, I came to the conclusion that gender identity was a shaky legal concept, that may also buy in to notions of gender essentialism; the notion that we’re born with gendered natures, and exhibit gendered behaviour, and have gendered abilities and interests.

There was a time when I would have said I feel like a woman, early in my transition. But I soon decided that was nonsense, that like most women I knew I felt like me, like a person. That my sense of gender came from context and relationship, and that it involved a lot of cultural stereotypes.

If I look at my earliest contributions to this online journal, I see myself characterizing female as being tender, vulnerable, brave, submissive, gentle, sensitive, having inner strength, nice, equanimous, empathic, loving one’s self, being flexible. Some of the qualities I associate with being male are being emotionally repressed, tough, dominant, cynical, obsessive, angry, stiff and bitter.

I am finding that the way forward is through practice and presence. Which for me right now, in more concrete terms, is gratitude and self love. Gratitude is a practice of presence, of experiencing the miracle of the moment. The trick is to let go, to be guided by sensation. The challenge is to be grateful for all my contradictions.

Self love I visualize more concretely, often in the negative, as in; “Don’t beat up on myself.” Don’t even beat up on myself for beating up on myself. As a friend said in a moment of inspiration, “We’re all miracles, spirit becoming gods, no wonder we find it so difficult.”

It is difficult to admit that the core of the problem is that the idea of being transgender, of having a gender identity is a woo woo idea. Gender identity is unverifiable, unscientific. Big value judgements here. And yet gender diversity exists, it’s an historical fact. I think all human cultures have had prescribed gender roles for the sexes, as well as people who transgress those roles.

I fear what I see as a push back from right wing and extremist religious forces, likely well funded, and for some reason inflaming the fears of some gender critical radical feminist thinkers. It's so divisive. We’re such a minority that I don’t see why radical feminists should be concerned at the far-fetched notion that trans women might dominate women only space, or positions reserved for women.

My view of being transgender, now, is that it is not something to be encouraged. It’s not something to take on lightly. I think we still know too little about it. I admire those who are gender queer, who reject gender identity. But society is so not ready, and the change demanded is so huge and fundamental I don't see much hope. If a person can find a way to live a reasonable life without transitioning, I think that’s best. Me, I’m questioning everything about being transgender. Except the fact that being a woman is the right thing for me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed